|

|

47 the real world DHJanzen100569.jpg high resolution

|

|

|

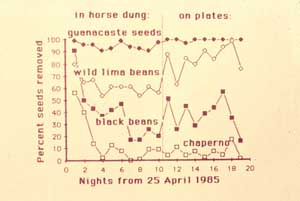

Large herbivore dung normally contains a mix of species of seeds (see image DHJanzen100570.jpg below for the actual seeds). How do these different seeds fare when Liomys finds that dung? The left half of this graph addresses that question. It is clear that the two species of highly desired seeds - guanacaste (a.k.a. Enterolobium cyclocarpum) and wild lima beans (a.k.a. Phaseolus lunatus) - were collected avidly from the dung (wild lima beans are quite small, and the fact that some survived is purely due to their small size and being lost to the mice). The two inedible seeds, black beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and chaperno (Lonchocarpus costaricensis, see above), were first collected by the mice as part of their learning process (see above) and then largely ignored. Now, contrast these results in dung, with that of the same species of seeds on bare plates, exposed to the same (now, knowledgeable) mice. They take all the Enterolobium seeds, and quickly build back up to taking all of the wild lima bean seeds (which, incidentally are very rich in cyanide, but the Liomys liver produces a cyanide-degrading enzyme, so they can eat them with impunity). The Lonchocarpus seeds continue to be ignored (the few taken are probably taken by naive mice in their learning process). The black bean seeds, however, are taken with increasing frequency, but erratically. What is happening? After some long thought, I realized that on some nights there was sufficient dew to wet the black bean seeds, and being commercial plants (long bred for quick germination), they began to swell and germinate overnight, making them then somewhat attractive to the mice, mice that largely ignore them in their hard dry state (ungerminated black beans are full of lectins, a defensive protein that the Liomys cannot readily digest, and the reason why you cook black beans). |

||

back to lecture slides

or skip to: